Sorry about delay correcting this, but the Articles page is now repaired

so that the links should take you to copies of each article on the PA website.

Try and see, and let us know if any other links are outdated!

Thanks

Mr. Scrivener

Showing posts with label Textual Evidence. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Textual Evidence. Show all posts

Monday, June 16, 2014

Friday, October 28, 2011

Luke 20:19 "the people" (ton laon) SWANSON

Re: Luke 20:19 "the people" (ton laon) SWANSON Swanson: Luke 20:19 (340-341) gives the following interesting set of variants: (in three pieces:) ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ λικμησει αυτον (19) Και εζητησαν οι γραμματεις και οι B A K L M U W Θ Π f1 f13 33 uw λικμησει αυτον (19) Και εζητουν οι γραμματεις και οι C λικμησει αυτον (19) Και εζητουν οι αρχιερεις και οι D 1071 λικμησει αυτον (19) Και εζητησαν οι αρχιερεις και οι πρεσβυτεροι και οι 69 λικμησει αυτον (19) Και εζητησαν οι αρχιερεις και οι Aleph Maj N Γ Δ Λ 2 28 157 565 579 700 1424 τ ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ αρχιερεις επιβαλειν επ αυτον τας χειρας εν αυτη ωρα, και εφοβηθησαν B A L M U W f1 f13 33 uw φαρισαιοι επιβαλειν επ αυτον χειρας εν αυτη ωρα, και εφοβηθησαν C γραμματεις επιβαλειν επ αυτον τας χειρας αυτη ωρα, εφοβηθησαν δε D αρχιερεις επιβαλειν επ αυτον την χειρα εν αυτη ωρα, και εφοβηθησαν K Π αρχιερεις επιβαλειν επ αυτον τας χειρας εν αυτη ωρα, και και εφοβηθησαν Θ γραμματεις επιβαλειν επ αυτον τας χειρας εν αυτη ωρα, και εφοβηθησαν 28 γραμματεις επιβαλειν επ αυτον τας χειρας εν αυτη ωρα, και εφοβηθησαν Aleph Maj N Γ Δ Λ Ψ 69 2 157 565 579 700 1071 1424 τ _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ τον λαον εγνωσαν γαρ οτι προς αυτους ειπεν την παραβολην ταυτην B Aleph-c L f13 157 uw τον λαον οτι προς αυτους ειπεν την παραβολην ταυτην Aleph* τον λαον εγνωσαν γαρ οτι προς αυτους ειρηκεν την παραβολην ταυτην D εγνωσαν γαρ οτι προς αυτους ειπεν την παραβολην ταυτην G εγνωσαν γαρ οτι προς αυτους την παραβολην ταυτην ειπεν S Y Λ Ω 565 700* 1424 τον οχλον εγνωσαν γαρ οτι προς αυτους την παραβολην ταυτην ειπεν N W Ψ τον λαον εγνωσαν γαρ οτι προς αυτους την παραβολην ειπεν 579 τον λαον εγνωσαν γαρ οτι προς αυτους την παραβολην ταυτην ειπεν A C Maj K M U Δ Θ Π f1 2 33 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ mr.scrivener |

Sunday, September 18, 2011

Pauline Interpolations (2) - 1st Cor. 11:3-16

'Pauline Interpolations' - 1st Cor. 11:3-16

Chapter 5 of Walker (2001) deals with 1st Cor 11:3-16.

It begins by noting that the passage "presents serious problems for the exegete".

He quotes G.D. Fee in support:

"it is full of notorious difficulties, including:However, the reader is not tipped off to Fee's actual position on this passage until several pages later: "Fee characterizes my proposal as a 'counsel of despair' " (i.e., Fee is against the interpolation argument).

(1) the 'logic' of the argument as a whole, which in turn is related to

(2) our uncertainty about the meaning of some absolutely crucial terms and

(3) our uncertainty about prevailing customs, both in the culture(s) in general and in the church(es) in particular (including the whole complex question of early Christian worship." (Fee, 1st Epistle to the Corinthians, p.492)

A review of Chapter 2 is required in order to fully assess the methodology of Walker, but those interested in textual criticism here will be interested in the short paragraph a few pages into this chapter (pg 95):

Wow! Internal evidence of whatever strength and nature trumps External evidence. Why? Because in the case of 'interpolations', no textual evidence is needed, and no evidence at all of an interpolation is worthless, because textual evidence is meaningless in the face of Internal evidence.2. Text-Critical Evidence for Interpolation

There is no direct text-critical evidence suggesting that 1st Cor. 11:3-16 might be an interpolation. The passage appears in all of the extant manuscripts - and indeed at the same location in all of the manuscripts. As was noted in Chapter 2, however, the absence of direct text-critical evidence for interpolation should be seen as precisely what it is: the absence of evidence. In the face of otherwise compelling arguments for interpolation, this absence of evidence should not be allowed to decide the issue."

The consequences of this need to spelled out. In cases where there are no textual variants, Walker is proposing that critics are free to chop, cut and paste the text, because textual evidence in favor of a given form and content of a document are powerless next to 'solutions' that can explain a passage or verse as an interpolation. This is 21st century textual reconstruction.

Picture how this methodology would work against the most important and difficult textual problems of the NT:

1) In case one were to argue that Mark's Ending was authentice, because its existance predates its omission, and every single ancient and modern copy of Mark has the verses, except two 4th cent. Uncials, even this is irrelevant, since "Internal Evidence" of whatever kind, makes all textual evidence, all patristic evidence, all versional evidence, moot.

2) In case one were to argue that John 7:53-8:11 was authentic, because it is referenced as Holy Scripture from the mid-300's forward, is quoted dozens of Early Christian Writers, and has been considered a part of the text of John for nearly 2,000 years, and that the structural, thematic, and linguistic evidence affirms its origin and position in John, we can throw all that out. What matters is whether the passage has 'features of an interpolation'. This will override any and all other forms of evidence and argument, even if that evidence is contradictory Internal Evidence!

Of course, many critics would love to practice a form of "reasoned eclecticism" that allowed such a free reign over the text. Each such critic would embrace the power power to pick and choose his own NT. But how far now have we strayed from any and every scientific historical-critical method, in adopting such a subjective, conjectural approach?

What has gone wrong here? Walker proposes erasing all distinction between conjectures about proto-texts, sources, methods of composition, and conservative textual criticism, which involves the assessment and application of actual hard historical documentary evidence.

In the past, textual criticism was distinguished as the task of discovering the original text, or at least arriving at the earliest and most primitive archetype, using the extant evidence, including manuscripts, patristic, and versional evidence. It was from the beginning recognized as having higher authority than mere conjectural exercises, or even ancient and respectable church traditions, never mind literary criticism.

Literary criticism was distinguished as an investigation into the composition of those texts, the detection of sources, authors' editorial and stylistic practices, motivations and concerns, purpose of writing, and the process of construction. This was openly admitted to be a 'softer science' type investigation, a nebulous, conjectural realm, with a tentative and provisional character.

In the past, Literary Criticism was a humble, if fascinating inquiry behind the scenes, with much the same authority as movie reviews and excursions into the intent of play-writers. It never exalted itself to the status of historical investigations, political analysis, economic theory, or theological construction.

But Walker seems to imagine that Literary Criticism now reigns supreme over even the hardcore historicity of extant manuscripts, patristic quotations, and versional disclosure.

mr.scrivener

Sunday, September 4, 2011

The Premature ABU Revised Version NT (1860)

Not to be confused with the American Sunday School Union, the American Bible Union (ABU) offered a series of books in the 1850-1880 period, notably:

1857 - The Book of Job ; the Common English Version the Hebrew Text and the Revised Version of the American Bible Union, by Conant, (ABU, 1857)

1858 - The Gospel According to Mark translated from the Greek on the basis of the Common English Version. With Notes.

1860 - Notes on the Greek Text of the Epistle of Paul to Philemon, as the basis of a Revision of the Common English Version; and a Revised Version, with notes. (anon., apparently written by Horatio B. Hackett) (ABU, 1860).

1861 - Tne Meaning and Use of BAPTIZEIN philologically and historically investigated, by CONANT, T.J.(1861), 8vo.

1865 - The New Testament of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ The Common English Version, Corrected By the Final Committee of the American Bible Union (1865, 2nd Revision, reprinted, 1873)

1868? - The Book of Genesis the Common Version Revised for the American Bible Union with Explanatory Notes, Conant (1868?)

1873 - Bible Primer, To Teach The Millions To Read God's Word. (Anon., ABU, 1873)

(A more complete list of these proto-Revised-Version attempts can be found here:

http://bibles.wikidot.com/abufirst-quartos

)

This earlier more conservative attempt at revision (pre RV 1881) shows more clearly what was originally intended by the Americans, and what sources were used.

Insight into the origin and intent of the American early revisers can be found scattered among the prefaces and introductions to these preliminary publications, as well in the the books independently published by these same authors.

For example, On page v. of the intro for the Gospel of Mark (1858), we get:

Critical Editions of the Greek Testament [consulted]:

1809 - Griesbach

1820 - Knapp

1830 - Fritzche GNT w. Comm.

1839[?] Bloomfield GNT w. Comm. [1839-1847]

1842 - Tittman, ed. Prof. Robinson NY

1846 - Lachmann [2nd critical ed]

1850 - Scholz (Bagster's)

1850 - Tischendorf [3rd ed.?]

1856 - Theile

As well as Five Editions of the TR:

1653 - Erasmus

1624 - Elzevir / 1707 - Mill (Bagster's)

1831 - Leusden (reprinted)

1831 - Prof. Wilson's ed.

???? - emendations from Robinson's Harmony of the Gospels.

IN that same edition, we are given the

General Rules for th Direction of Translators and Revisers employed by the ABU"

" 1. The exact meaning of the inspired text, as that text expressed it to those who understood the original Scriptures at the

time they were first written, must be translated by corresponding words and phrases, so far as they can be found, in the vernacular

tongue of those for whom the version is designed, with the least possible obscurity or indefiniteness.

" 2. Wherever there is a version in common use, it shall be made the basis of revision, and all unnecessary interference with

the established phraseology shall be avoided ; and only such alterations shall be made as the exact meaning of the inspired text

and the existing state of the language may require.

" 3. Translatious or revisions of the New Testament shall be made from the received Greek text, critically edited, with known

errors corrected.

"SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS TO THE REVISERS OF THE ENGLISH NEW TESTAMENT.

"1. The Common English Version must be the basis of the revision: the Greek Text, Bagster & Sons' octavo edition ['TR' = Scholz]

of 1851.

" 2. Whenever an alteration from that version is made on any authority additional to that of the reviser, such authority must

be cited in the manuscript, either on the same page or in an appendix.

" 3. Every Greek word or phrase, in the translation of which the phraseology of the Common Version is changed, must be

carefully examined in every other place in which it occurs in the New Testament, and the views of the reviser be given as

to its proper translation in each place."

-------------------

These rules seem to have allowed an unforeseen degree of freedom in regard to the original Greek, an ambiguity which other parts of the rules clearly intended to avoid (the potential for and real abuse of such well-intended rules in regard to the English Revised Version is well-documented).

But in spite of conservative sentiments and attempts to contain revision within reasonable limits, there was an ethos, a rather less precise and dangerously vague attitude among these early revisers, which left them and their work open to tragic errors in their handling of the NT text.

We can find revealing glimpses of some of this attitude in other publications, not directly under control of the ABU.

For instance, Horatio b. Hackett had already published:

1858 - A Commentary on the Original Text of the Acts of the Apostles H.B. Hackett (revised 1858),

On the one hand, Hackett encourages a healthy Protestant historical/critical approach. In regard to Acts, he says,

"No person can be prepared to read the Epistles of the NT with the greatest advantage until he has made himself familiar with the external history of the Apostle Paul, and with his character and spirit, as Luke has portrayed him in his narrative. Those portions...must be thoroughly mastered before any proper foundation is laid for exegetical study of the Epistles."Again, Hackett explains,

"It is the object of these notes to assist the reader in the acquisition of this knowledge and discipline; to enable him to form his own independent view of the meaning of the sacred writer..., and at the same time, furnish himself to some extent with those principles and materials of criticism which are common to all parts of the Bible. ...and to promote a habit of careful study and of self-reliance ...a result beyond any other which the writer has been anxious to accomplish. ...The grammatical references and explanations will enable the student to judge of the consistency of the interpretations given with the laws of Greek language. The authorities cited will show the state of critical opinion on all passages that are supposed to be uncertain or obscure."(- H.B. Hackett, Preface to Acts, Newton Theol. Inst., Oct 31, 1851)

So far, so good. But now let us turn to another book, perhaps where Hackett has expressed himself in a more unguarded fashion. In his Notes on the Greek Text of the Epistle of Paul to Philemon, (ABU, 1860), Hackett explains more clearly his idea of Bible translation:

"An exposition of the text, as a mental process at least, on the part of the interpreter (though the results may not be written out), must precede a translation. The Notes, therefore, here laid before the reader, have the same interest and value as a means of understanding the text of the Epistle, as if they were unaccompanied by a revision of the Common English Version.

But the other portion of the work has also its separate claims on the attention of the Biblical student. An addition of this nature has become, within a few years, a common feature in the best exegetical works published in this country, and in

England. The fact sets forth an important truth. It is felt more and more that critical attempts to explain the meaning of the Scriptures should, as the proper test of their definiteness and precision, terminate in an endeavor to express the sense as nearly as possible in our own language ; and furthermore, that they must assume this form, in order to render such studies available in any great degree to the bulk of English readers.

The topic last suggested here deserves a word further. This matter of the history of the current translation of the Bible, and a comparison of its renderings, with those of the preceding translations,* out of which the Common Version has arisen, are opening to us a range of study, comparatively new and attractive certainly to those who enter upon it. Some of the best scholars of the day are giving their attention to it. The student of English literature will reap profit as well as gratification from it.

The different epochs of our language are well marked in the style of the different versions. We learn, thence, that the English race, even since the dawn of Protestantism, and during some of the most effective periods of the national development, have not been dependent upon any single translation of the Bible, but have received their knowledge of the gospel through various channels. It is no disservice to be taught that the power of Christianity resides in its doctrines and ideas, and not in any set of words or phrases which it may outgrow with the advance of Biblical science, and the mutations of language, and must then, or should, discard for other forms. It is seen from such recurrence to the past, to be the wisdom of the church, to which have been committed the Oracles of God, to open promptly every source of religious knowledge to the many as well as the few. The names of Wiclif, Tyndale, Frith, Coverdale, are witnesses how slowly this truth has made its way in the world, in regard to the use and treatment of translations of the Sacred word into the vernacular tongue of a people. The history of the English Bible has been, from first to last, a singular history of conflicts between an excessive conservatism on the one hand, and the promptings of a more expansive religious spirit on the other, and a history, at the same time, of victories on the side of truth and progress. It is well that the public mind is turning itself back to inquiries which are so interesting and adapted to reassert and enforce principles of vital importance.

There is much misapprehension still, I imagine, respecting the precise nature of the enterprise, in the interest of which this volume has been prepared. The object is not to supersede, but revise the current Version of the English Scriptures. A new translation of the original text, and a revision of the translation of that text, are very diflferent things; and yet, different as they are, are confounded by many persons who would not be unfriendly to what is attempted, if they would keep in mind this important distinction. It is not proposed to discard the present Version; to cast away its manifold advantages ; to introduce rash and doubtful innovations ; to substitute a cumbrous Latinized style for the simple, nervous, idiomatic English, which brings the familiar Version so home to the hearts of the people ; but simply to do upon the work of our translators what they did upon that of their predecessors; to survey it afresh in the light of the knowledge which has been gained during the more than two centuries since they passed away ; to make such changes, and such only, as the general verdict of the best scholarship of the age has pronounced to be due to truth and fidelity ; to make these changes in a style of delicate harmony with the present language of the English Bible ; to confirm its accuracy, where it is correct, against false or unsupported interpretations, as well as to amend it where it is confessedly incorrect ; and thus, in a word, carry forward from our position, if we might, the labors of the revisers (for such they were) of James' age, as they carried forward the labors of the generations before them.The important idea here is the concept of "dynamic" or idiomatic translation, although it is not yet articulated with any sensible scientific restraint. The view promotes the idea of multiple forms of verbal expression, i.e., with all translations being somehow equal or equally inspired.

On some other occasion I may have an opportunity to speak of the Greek text on which the revision is founded, and some other kindred topics. I have endeavored to unfold the contents of the Epistle with candor and impartiality, and would hope that those who may examitie the work will judge of it in the same spirit. ...

------------------------------------

* It can not have escaped notice that the various English readings have began to form an important new material in our works of Biblical criticism. Professor Alexander of the Princeton Theological Seminary, whose recent death is a calamity to the cause of sacred learning, has enriched greatly his New Testament Commentaries by his copious illustrations of this character. "

Certainly accuracy and precision in translation indeed requires idiomatic forms, and may also require language updating as language evolves. But the dangerous effect of free expression, namely corrosion of meaning and the authority of the written, inspired word of God, has simply not yet occurred to American Protestants (c. 1860s).

The natural evolution of the unrestrained idea, is that if God's word can have many forms, and if some forms seem contradictory, or remove, or add to other forms, these forms can be and must be error-prone, if not error-ridden. Its a short step from here to assigning an equally low priority and accuracy to ANY form of the word of God, with the attendant consequences, namely that people will pick and choose what they perceive to be "the word of God", inevitably selecting what is convenient and appealing, while rejecting what is inconvenient or unappealing. Which is precisely the state of confusion over modern 'versions' that we have now.

mr.scrivener

Thursday, July 28, 2011

Sturz (3): Byzantine-Papyrus Readings John

Continuing List 1 with Readings from John's Gospel:

1:39 ηλθαν * και P5 P ΓΔΠ unc9 700 pm c f q vg arm Κ ς

2:15 ανεστρεψεν P75 ALPΓΔΛΠ* unc9 pl (Or) Κ ς

2:24 εαυτον αυτοις P66 אc A2 PWΓΔΘΛΠ unc9 pm it-pc vg Or-pt Κ ς

4:14 διψηση P66 C3W ΛΠ unc8 pm Κ ς

4:31 εν δε τω P75 AC3ΓΔΘΛΠ unc8 pl b f ff2 m q co cy-cp (Or) Chr Cyr Κ ς

5:37 αυτος P66 AΓΔΘΛΠ unc8 pl lat sy Eus Κ ς

6:10 ωσει (P28)P66() AΓΔΘΛΠ unc9 λ φ pl Κ ς

6:57 ζησεται P66 EGHMSUVWΓΔ(Θ)ΛΠ(Ω) (unc7) λ pm lect.1561 Κ ς

7:3 θευρησωσι P66 B3XΓΔΛΠ unc8 λ pm Κ ς

7:39 πνευμα αγιον P66 LNWXΓΔΛ unc6 λ φ 33 1241 pl (sa) (0r) Ath Did Chr Cyr... Κ ς

7:40 Πολλοι P66 ΓΔΛΠ unc7 118 pl f q go sy Κ ς

8:21 αυτοις ο Ιησους p66c ΓΔΘΛΨ unc8 λ φ 33 pm lat co Chr Κ ς

8:51 το λογον τον εμον P66 ΓΔΘΛΠ unc8 λ φ pm latt sy Κ ς

8:54 δοξαζω P66 אc C2LXΓΔΛΠ unc8 pl Κ ς

9:16 αλλοι P66 P75 ALXΓΔΘΛΠ unc8 28 pm it-pl (vg) go arm sy-p Chr Κ ς

9:19 αρτι βλεπει P66 AXΓΔΛΠΨ unc7 λ φ 565 579 1241 pm co lat Κ ς

9:26 αυτω παλιν p66 AXΓΔΘΛ unc8 λ φ pl f q go (sy) arm eth Cyr Κ ς

9:28 ελοιδορησαν P66 AX ΓΔΛ unc8 φ (-69) 28 al b e l q (vg) arm Aug Κ

9:35 ειπεν αυτω P66 אcAL(X auton) ΓΔΘΛ unc7 pl sy-s lat Κ ς

10:19 σχισμα ουν παλιν P66 AΓΔΘΛΠΨ unc7 λ φ pl (bo) sy-p Chr Cyr Κ ς

10:29 ος P66 P75 AB2MUX ΓΔΘΠ (Λ ous) unc8 λ φ 33 565 pl sa sy-sph eth Κ ς

10:29b μειζων παντων εστι p66 AΓΔΘΛΠ unc8 λ φ 33 565 pl lat go sa sy-sph Bas Dial Chr Κ ς

10:31 εβαστασαν ουν παλιν P66 AXΠ unc-rell λ 565 pl (sy) Κ ς

10:32 πατρος μου P66(P75)אc ALWX unc-rell λ φ pl lat Κ ς

10:38 πιστευσατε P45 P66 AEGHMSXΓ Λ λ φ 118 209 pl Ath Bas Chr Κ ς

10:38b αυτω P45 AΓΔΘΛΠ unc7 λ φ pl b f ff2 l go sy-p Cyp Κ ς

11:19 προς τας περι (P45) AC3ΓΔΘΛΠΨΩ unc7 λ φ 565 pm Κ ς

11:21 μαρθα P45 AΓΔΛ unc7 pl Κ ς

11:21b ο αδελφος μου ουκ αν P45 P66 C3ΓΔΘΛΠΩ unc8 φ pl Κ ς

11:29 εγειρεται P45 P66 AC2ΓΔΘΛΠ unc8 λ φ pm l vg Κ ς

11:31 λεγοντες P66 AC2ΓΔΘΛΠΨ unc8 pm it vg sa sy-ph Κ ς

11:32 εις P66 AC3ΓΔΘΛΠ unc8 φ pl Κ ς

11:32b απεθανεν μου ο αδελφος P45 AC3XΓΛΠ unc8 λ (φ) pl Κ ς

12:6 ειχεν και P66 AIXΓΔΛΠΨ unc8 pl a b c f go arm Κ ς

12:9 οχλος πολυς P66 P75 AB3IQXΘΨ λ φ 33 pl f g vg bo go sy-ph Κ ς

12:36 εως P66 XΓΔΛΠ3 unc8 λ φ 1241 pm Κ ς

12:36b ο Ιησους P75 אcAXΓΔΛΠ unc8 rell Libere Chr Κ ς

13:26 και εμβαψας P66 AWΓΘΛΠΨ unc8 λ Κ ς

13:26b ισκαριωτη P66 AWΓΔΛΠ* unc7 λ φ pm vg-c go co arm Or Κ ς

14:5 δυναμεθα την οδον ειδεναι P66 AC2LNQWXΓΔΘΛΠ unc6 λ φ pl it-pc vg Κ ς

19:4 εξηλθεν ουν P66c EGHMSUWYΔΘΛ φ pm Κ ς

19:11 απεκριθη αυτου P66c AXYΔΛΠ unc6 φ pm it-pc vg go co arm sy-p Κ ς

19:35 εστιν αυτου η μαρτ. P66EGKSUΛ 579 pm am ing Caes Κ

20:17 πατερα μου P66 ALOXΓΔΘΛΠ unc6 λ φ pl lat sy-ps sa bo Κ ς

Friday, July 22, 2011

Sturz (2): Byzantine-Papyrus Readings Luke

Here again are examples from Sturz' List 1, (cont.)

Distinctively Byzantine - Papyrus Alignments (Byz Text-type p. 145 fwd):

Luke:

6:28 καταρωμενους υμιν P75 EHLSUVΔΘΛ pm Just (Or) Κ ς

6:39 δε P45 [P75] APΓΔΛΠ unc7 pl co go sy-p Κ ς

9:30 μωσης P45 AEGHMPSUVΓΛ λ pm (Κ) ς

10:21 τω πνευματι P45 AEGHMSUVWΓΔΛ φ pl f g bo-pt Cl Bas Cyr Κ ς

10:39 του ιησου P45 P75(-του) AB3C2PWΓΔΘΛΠ unc9 λ φ pl b sy-ptxt Bas Κ ς

11:12 η και εαν P45 AWXΓΔΘΛΠ unc9 pl Κ ς (ΑΘΛ pc αν)

11:12 αιτηση P45 EFGMSUVWXΠ φ pm Κ ς

11:33 το φεγγος P45 ALWΓΔΛΠ unc8 28 33 pm Κ ς

11:50 εκχυνομενον P75 HKMSVXΓΘΛ λ pl Κ ς

12:5 εξουσιαν εχοντα P45 EGHMSUVΓΔΛ pm eth Tert Κ ς

12:21 εαυτω P75 AQXΓΔΘΛΠ λ unc9 pl Κ ς

12:22 ψυχη υμων P45 XΓΔΛΠ unc8 φ pl a e g2 vg-ed sy-c sa bo eth Cl Ath Κ ς

12:23 η ψυχη P45 AEGHKQUVWΓΔΛΠ pl a f ff2 i q g-l vg sy-ptxt Κ ς

12:30 επιζητει P45 AQWΓΔΘΛΠ unc8 λ pl Bas Ath Κ ς

12:31 την βασιλειαν του θεου P45 AD2QWXΓΔΘΛΠ 070 unc8 λ φ pl d it-pl vg sy-c Cl Mcion Κ ς

13:2 οτι τοιαυτα P75 AWXΓΔΘΛΠ 070 unc8 λ (φ) pm it vg Chr Κ ς

13:19 δενδρον μεγα P45 AWXΓΔΘΛΠ unc9 λ φ pl c f q sy-p eth Κ ς

13:28 οψησθε P75 AB2LRWΓΔΛΠ 070 unc8 pl it vg Ir Κ ς [WH]

14:3 ει εξεστιν P45 AWXΔΛΠ unc8 λ φ pl it-pl vg (sa) sy-c Κ ς

14:23 ο οικος μου P45 PWΓΔΛ unc8 λ φ pl lat Bas Κ ς

14:34 εαν δε P75 ARWΓΔΛΠ unc8 pl e ff2 i vg-ed co sy-p eth arm Κ ς

15:21 υοις σου P75 ALPQRWΓΔΘΛΠ unc7 λ φ pl it (vg) go co sy-h arm Aug Κ ς

15:22 την στολην P75 D2EGHK2MRSUVXΓΔΛ pl Ps Chr Dam Κ ς

23:53 εθηκεν αυτο P75 ALPWXΓΔΘΛΠ unc8 pl c Κ ς

24:47 αρξαμενον P75 AC3FHKMUVWΓΔ* ΛΠ λ φ pm (a c e l) (sy-sp) arm Κ ς

Sunday, June 26, 2011

Textual Critical Websites: Analysis

Monday, May 30, 2011

W. L. Richards' review of K.D. Clarke's "Textual Optimism"

Richards in 2002 offered a review of Clarke's book (avail. on the internet in .pdf).

What is good about the review is that it gives a good summary of the contents and position of Clarke's book:

mr.scrivener

Textual Optimism: a Critique of the United Bible Societies' Greek New Testament

What is good about the review is that it gives a good summary of the contents and position of Clarke's book:

"The basic thesis of Clarke’s evaluation of the upgrading of “certainty” in the rating of variants by the editors in UBS 4 over the three previous editions is not only overly optimistic, as the title of his book suggests, but also is methodologically inconsistent and devoid of delineated criteria for making these optimistic judgments.

As a background to his investigation of the ratings within the United Bible Societies Greek New Testament (UBS), Clarke provides in chapter 1 a helpful overview of the textual tradition behind the four editions, beginning with the contributions of Westcott and Hort and continuing with key developments since their time. Of particular value is the specific information lying behind each of the four UBS editions as well as helpful information as to how the UBS text and the Nestle-Aland text eventually ended up being the same. Clarke tabulates in two columns some important differences that remain between the UBS and Nestle-Aland critical editions (68-9).

In chapter 2 the author focuses on the differences of the rating in UBS 4 as compared to the first three editions, providing many charts (drawn from several appendices) showing the number of modifications in UBS 4 with the previous editions. The massive amount of statistical data bears out Clarke’s contention that UBS 4 represents the text of the Greek NT as far “more certain” than the previous editions. H is first ch art, for example, shows that UBS 4 has approximately four times as many A readings as were given in the previous UBS editions (514 to 136 or less). Correspondingly, UBS 4 shows a significant decrease in the number of C and D readings: 27 percent of the total in UBS 4 as compared to 58 percent in UBS 3 ( the first two ed itions differ slightly form UBS 3 ).

This results in the number of B read ings rem aining nearly the same in all four editions, and this is to be expected, for while ma ny of the form er B readings have been elevated to A status in UBS 4 , many of the former C and D readings have also been elevated, leaving us with approximately the same number of B readings. But whereas the percentage of B readings is the same, the readings com prising the new totals are quite d iffere nt. What used to be a four-step rating system (A-D) has now become a three-step system (the D rating now makes up just one percent in the UBS4 as compared to nine percent in the previous editions (91).

...

Clarke repeatedly asks why the UBS4 editors did not account for these major shifts toward certainty, holding that the explanation given in the introduction to the fourth edition for the changes is insufficient. But more, he believes that the shifts were made as a result of flawed methods and logic. Major proof for this comes in his analysis of the only two texts in UBS 4 that were given a three-step upgrade (D to A): Luke 19:25 and Acts 2:44. His point is that if the committee could make such a major upgrade in these two places where, upon analysis, Clarke concludes they should not have, how can we trust their judgments elsewhere? (155 fn and 1 76).

...

(As a matter of interest to me, for years I felt that the ratings in UBS 1-3 were often too cautious, frequently making my own upgrades in the classroom, and, interestingly, doing so on precisely the same grou nds used by Clarke to draw his negative conclu sions about the optim ism of the editors of UBS4 , namely, “the recognized principles of New Testament textual criticism” [14].)

The questions raised by Clarke are important apart from the fact that one may not agree completely with his conclusions."

(excerpted from Richards, Book Review)

mr.scrivener

Thursday, May 5, 2011

Vaganay (1935) on Tischendorf

The following is taken from the English translation of Vaganay (1935) An Introduction to NT Textual Criticism (1991, Cambridge) transl. Amphoux/Heimerdinger, p. 148 fwd:

"In point of fact, the text itself was not so important. Tischendorf had essentially no firm principles from which to work. He was an enthusiastic and fortunate explorer, an active and vigilant editor, an ardent collector of variants, but he did not have a critical mind, in the true sense of critical. Generally speaking, he continued in the tradition established by Lachmann, giving preference to the earliest Greek texts but he paid only scant attention to their classification into families. He appeared indeed to mistrust any theory about the history of the text, preferring to rely on his own judgement to decide between several early variants. He was unfortunately always influenced by the last manuscript he happened to have studied. Everyone acknowledges, for example, that in his last edition he set too much store by Codex Sinaiticus. Besides, he did not have time to write his own Prolegomena. This was left to one of his disciples, C. R. Gregory, who published his Prolegomena, a superb work of textual criticism, as an appendix to the Editio Octava maior (vol III, 1884; re-edited and enlarged, 1894).Caspar Rene Gregory also continued the work of compiling a list of the NT manuscripts, giving a brief description of each. The result is a work of fundamental importance: Textkritik des Neuen Testamentes in three volumes (1900-09). The first deals with the Greek MSS, adopting the nomenclature used by Tischendorf which goes back to Wettstein. The 2nd volume contains the earlier MSS of the various early versions [translations]. Finally, the 3rd contains additions to the other 2 volumes and adopts a new system of numbering the Greek MSS which consists entirely of figures and which is still in use today. There were two people who took over the work from Gregory, E. von Dobschutz and K. Aland (see p. 10). In just one century, the # of MSS has doubled. For the MSS of the versions, except for the Latin, there is still no successor to Gregory; the situation at present is that each editor uses his own signs or somebody else's, thus causing a certain amount of confusion.In conclusion, it may be said that Tischendorf did not really contribute to the improvement in method of NT TC. He simply introduced an element of flexibility into the method of his predecessors in allowing more room for internal criticism. Honour is due to him rather for the discovery and the edition of new witnesses to the text. He was, above all, a man of learning, and, so to speak, a man of the variants. It was Gregory who was to be the man of the documents. There are, it is true, many errors in the lists they compiled, even though great care was taken. On the whole, they represent a monument which is neither bold in its design nor balanced in its proportions, but it is a least solid in its foundations." (ch. 4, p. 143-148).

mr.scrivener

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

Sad Truth: The Missing MSS of the 4th - 14th centuries

In the following concise account, we can simultaneously learn about the switch from papyrus, the preference for parchment, and the destruction of the bulk of ancient gospels all in one pass. Here we can read another large piece of the heartbreaking puzzle of what happened to the thousands of Gospel manuscripts made between the 4th and 10th centuries:

“Paper came before its time and had to wait for recognition. It was sorely needed. The Egyptian manufacture of papyrus, which was in a state of decay in the 7th century, ceased entirely in the 9th or 10th. Not many books were written during this period, but there was then, and for at least three centuries afterwards, an unsatisfied demand for something to write upon. Parchment was so scarce that reckless copyists frequently resorted to the desperate expedient of effacing the writing on old and lightly esteemed manuscripts. It was not a difficult task. The writing ink then used was usually made of lamp-black, gum and vinegar; it it had but a feeble encaustic property, and it did not bite in or penetrate the parchment. The work of effacing this ink was accomplished by moistening the parchment with a weak alkaline solution and by rubbing it with pumice stone. This treatment did not entirely obliterate the writing, but made it so indistinct that the parchment could be written over the second time. Manuscripts so treated are now known as palimpsests. All the large European public libraries have copies of palimpsests, which are melancholy illustrations of the literary tastes of many writers or bookmakers during the Middle Ages. More convincingly than by argument they show the utility of paper. Manuscripts of the Gospels, of the Iliad, and of works of the highest merit, often of great beauty and accuracy, are dimly seen underneath stupid sermons, and theological writings of a nature so paltry that no man living cares to read them. In Some instances the first writing has been so thoroughly scrubbed out that its meaning is irretrievably lost.“Much as paper was needed, it was not at all popular with copyists; their prejudice was not altogether unreasonable, for it was thick, coarse, knotty, and in every way unfitted for the display or ornamental penmanship or illumination. The cheaper quality, then known as cotton paper, was especially objectionable. It seems to have been so badly made as to need governmental interference. Frederick II, of Germany, in the year 1221, foreseeing evils that might arise from bad paper, made a decree by which he made invalid all public documents that should be put on cotton paper, and ordered them within two years to be transcribed upon parchment. Peter II, of Spain, in the year 1338, publicly commanded the paper-makers of Valencia and Xativa to make their paper of a better quality and equal to that of an earlier period.“The better quality of paper, now known as linen paper, had the merits of strength, flexibility, and durability in a high degree, but it was set aside by the copyists because the fabric was too thick and the surface was too rough. The art of calendering or polishing papers until they were of a smooth, glossy surface, which was then practised by the Persians, was unknown to, or at least unpractised by, the early European makers ...

mr.scrivener“There is a popular notion that the so-called inventions of paper and xylographic printing were gladly welcomed by men of letters, and that the new fabric and the new art were immediately pressed into service. The facts about to be presented in succeeding chapters will lead to a different conclusion. We shall see that the makers of playing cards and of image prints were the men who first made extended use of printing, and that self-taught and unprofessional copyists were the men who gave encouragement to the manufacture of paper. The more liberal use of paper at the beginning of the 15th century by this newly-created class of readers and book-buyers marks the period of transition and of mental and mechanical development for which the crude arts of paper-making and of black printing had been waiting for centuries. We shall also see that if paper had been ever so cheap and common during the Middle Ages, it would have worked no changes in education or literature; it could not have been used by the people, for they were too illiterate; it would not have been used by the professional copyists, for they preferred vellum and despised the substitute.“The scarcity of vellum in one century, and its abundance in another, are indicated by the size of written papers during the same periods. Before the sixth century, legal documents were generally written upon one side only; in the tenth century the practice of writing upon both sides of the vellum became common. During the thirteenth century valuable documents were often written upon strips two inches wide and but three and a half inches long. At the end of the fourteenth century these strips went out of fashion. The more general use of paper had diminished the demand for vellum and increased the supply. In the fifteenth century, legal documents on rolls of sewed vellum twenty feet in length were not uncommon. All the valuable books of the fourteenth century were written on vellum. In the library of the Louvre the manuscripts on paper, compared to those on vellum, were as one to twenty-eight; in the library of the Dukes of Burgundy, one-fifth of the books were of paper. The increase in the proportion of paper books is a fair indication of the increasing popularity of paper; but it is obvious that vellum was even then considered as the more suitable substance for a book of value.” (- De Vinn, quoted for review from "Medieval Ink")

Sunday, April 17, 2011

Secret MS Stashes awaiting 'discovery'

As paradoxical as it may sound, a probable majority of surviving manuscripts remains inaccessible to the public and unknown to scholars. Nonetheless, they could become known at any time, as various wealthy private collectors die, and their estates are redistributed and the items auctioned off. Its an ongoing process.

A large number of MSS soon to be "discovered" are of this type, rare objects remaining in private hands, and because of perhaps doubt as to the method of acquisition and legitimacy of ownership, will only slowly trickle out.

The various nefarious stories surrounding more recent 'discoveries' and purchases via international 'dealers' (DSS, Nag Hammadi etc.) is really only the tip of an iceberg of stories and events affecting the movement and preservation of such treasures.

The description of the story of the personal collection of Leander van Ess, recently posted on the internet by Milton Gatch, gives a picture in microcosm of the political and religious events which expose ancient MSS to market forces:

One can imagine, with some 100 wars and conflicts raging round the world at any time since the two World Wars (another story of vast displacements) just how frequent the transfer of goods, and sometimes loss, is occurring today.

mr.scrivener

|

| A Book of Hours: many thousands sit in private hands |

A large number of MSS soon to be "discovered" are of this type, rare objects remaining in private hands, and because of perhaps doubt as to the method of acquisition and legitimacy of ownership, will only slowly trickle out.

The various nefarious stories surrounding more recent 'discoveries' and purchases via international 'dealers' (DSS, Nag Hammadi etc.) is really only the tip of an iceberg of stories and events affecting the movement and preservation of such treasures.

The description of the story of the personal collection of Leander van Ess, recently posted on the internet by Milton Gatch, gives a picture in microcosm of the political and religious events which expose ancient MSS to market forces:

What is remarkable is how, just as recently as 180 years ago, miltary/political events (the rise and fall of Napoleon) caused the massive displacement and exchange of hands of perhaps the majority of MSS then residing in monasteries in the West, i.e., France and Germany. The well-known (?) temporary capture of Codex Vaticanus by Napoleon was only one MS transport case, but Napoleon actually caused the movement of many thousands of books and manuscripts."Although he was never a wealthy man, historical circumstances made it possible for Leander van Ess to acquire large collections of valuable books. He emerged from the monastery into the world because of the secularizing programs of the Napoleonic regime in Germany at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The dissolution of the monasteries involved the dislocation of extensive and ancient libraries. In some areas of Germany these books were gathered into university or royal libraries, but in northwestern Germany there were no such repositories and the holdings of monastic libraries, if not taken to France by the conquerors, were thrown open (as it were) to the world. They were sometimes taken by the former monks as they went on to other lives; often they found their way to the open market, sometimes under questionable circumstances.Leander van Ess amassed very large collections, apparently at nominal expense. He had books from Marienmunster, acquired when he left there; he had books from other former monastic libraries, including many from the Benedictine monastery at Hysburg in the diocese of Halberstadt, of which his cousin Carl had been a member. A large number of books originating from a number of south-west German monasteries, came from the duplicates collection of the unversity library at Freiburg im Breisgau. A significant group of manuscripts originated at the Carthusian monastery of St. Barbara in Cologne. Van Ess continued to acquire books at Schwallenberg, during his tenure at Marburg, and at Darmstadt.By happy chance, most of the books once owned by Leander van Ess can still be identified. They are the collection of manuscripts and incunabula sold in 1824 to the great English collector, Sir Thomas Phillipps (1792-1872) and van Ess's library, sold in 1838 to Union Theological Seminary in New York." ( - Milton Gatch)

One can imagine, with some 100 wars and conflicts raging round the world at any time since the two World Wars (another story of vast displacements) just how frequent the transfer of goods, and sometimes loss, is occurring today.

mr.scrivener

Monday, March 21, 2011

Codex W and Greek Enoch? ...I don't think so

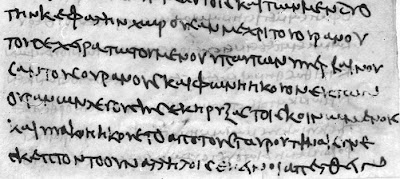

In his palaeographic analysis, Sanders (1912) compared Codex W to several older Greek manuscripts, including P. Cair. 10759. (Greek Enoch, Gosp.Peter etc.). To give a standard sample for manuscripts of this early period, we offer the following example, P. Chester Beatty XII, leaf 3:

The first thing to note about early calligraphy, is the startling difference between using a soft brush or reed (earlier papyri) and using a hard nib or quill (4th - 5th century and beyond). This stylizes the writing more than any other single factor. Its the difference between painting, which is soft and blob-like, allowing the ink/paint to flow and leading it with the brush, versus the firm and hard controlled strokes of the pen, using a thinner more ink-like medium.

This softer paint-like writing was practically necessary, because of the relative roughness and fragility of papyrus, which was a primitive paper-like material, as opposed to later parchment and vellum (animal skins).

It is true that sometimes the early Egyptian scribe using papyrus would give a slight to moderate tilt or angle to the letters, but this varies from scribe to scribe, and can hardly be defined even as a conscious choice. The tilt is probably based on practical factors like right- or left-handedness, and not issues of style at all. The early slight to moderate tilt may be quite noticeable in more extreme cases, but does not seem to be a choice based on anything but writing convenience and speed. There is no dispute however, that slanted writing was popular quite early, as a few samples of P45 can illustrate:

Again, the thickness of the letters may vary widely, from elegant like this, to bloated and clumsy, but the same 'painted on' look dominates the calligraphic style and feel, regardless of incidentals like letter-shape or tilt. As well, P45 (or the group of pages so designated) involves a variety of books and hands, all dated roughly to the 3rd century, of which only Luke/Acts is tilted. It is not possible to make any conclusion at all regarding date based on tilt or angle of writing.

P45 wasn't available to Sanders (P45 was discovered in 1930), but probably would have been preferred by him as an example of early slanted writing over the Greek Enoch fragments from P. Cair. 10759 below:

P. Cair. 10759 also spans several books and hands, but the Enoch pages have the closest similarity to Codex W. Of particular interest is one feature, namely the variation in line thickness based on the angle of the 'nib' or quill used to write the letters. This itself seems to suggest a much later date for this section of 10759, than may have been at first assigned to it. The other pages (e.g. Peter) show instead the typical 'painted on' look of a brush-like implement or soft quill. Indeed, Enoch resembles more the typical hand of the late 3rd or 4th century scriptorium than the early papyri.

We have already referred to Schmid's excellent and thorough article in The Freer Biblical Manuscripts (2006), Ed. Larry W. Hurtado, and we will quote his passage of Sanders here:

Here Sanders is already jockeying to secure an earlier date for his Codex W, but the problem of the anachronism of P. Cair. 10759 is quite glaring! - It has already been dated to the 6th century A.D., and yet it is probably the closest thing to Quire 1 of John in Codex W we are ever going to find. In other words, despite Sanders' cleverness, this is really evidence for dating W to the 6th century palaeographically, not the 5th century.

And if so, trying to make Codex W the archetype of other 5th/6th century witnesses is a naive and flimsy proposal. But why does it matter? Because Codex W is now no longer an early "4th or 5th century" witness to other palaeographic features, such as outdented and enlarged letters, slanted varying-width styles, etc. - But rather, a very late witness.

mr.scrivener

|

| Typical earlier Greek Papyrus: Click to Enlarge |

|

| paint-brush versus quill - Click to Enlarge |

This softer paint-like writing was practically necessary, because of the relative roughness and fragility of papyrus, which was a primitive paper-like material, as opposed to later parchment and vellum (animal skins).

It is true that sometimes the early Egyptian scribe using papyrus would give a slight to moderate tilt or angle to the letters, but this varies from scribe to scribe, and can hardly be defined even as a conscious choice. The tilt is probably based on practical factors like right- or left-handedness, and not issues of style at all. The early slight to moderate tilt may be quite noticeable in more extreme cases, but does not seem to be a choice based on anything but writing convenience and speed. There is no dispute however, that slanted writing was popular quite early, as a few samples of P45 can illustrate:

|

| P45 - Click to Enlarge |

P45 wasn't available to Sanders (P45 was discovered in 1930), but probably would have been preferred by him as an example of early slanted writing over the Greek Enoch fragments from P. Cair. 10759 below:

Papyrus Cairo 10759

|

| Gospel of Peter (Click to Enlarge) |

| |

| Enoch (Click to Enlarge) |

We have already referred to Schmid's excellent and thorough article in The Freer Biblical Manuscripts (2006), Ed. Larry W. Hurtado, and we will quote his passage of Sanders here:

"Hand 'c' [of Enoch] bears a much closer resemblance to the hands of W...The ease, grace, and slope of the hand remind one strongly of the first hand of W, but the shapes of many of the letters, notably γ ε κ μ σ ω are far closer to [the 1st quire of John in W]. I see no reason for not considering the two hands of the Enoch fragment contemporary. It [Enoch] has been dated to the 6th century, but though both hands are somewhat more developed types than the hands of W, I should not place the date later than the end of the 5th [century]." (Sanders, 137-8, in Schmid, p. 239)

And if so, trying to make Codex W the archetype of other 5th/6th century witnesses is a naive and flimsy proposal. But why does it matter? Because Codex W is now no longer an early "4th or 5th century" witness to other palaeographic features, such as outdented and enlarged letters, slanted varying-width styles, etc. - But rather, a very late witness.

mr.scrivener

Monday, March 14, 2011

Redating Codex W based on the Obvious...

| |

| Click to Enlarge: Use Backbutton to return |

Like Codex Sinaiticus, the seeming 'newness' of the MS raises an eyebrow next to others of supposed similar date.

Even the burnt edges look suspiciously like either (relatively recent?) fire-damage, or else the kind of oxidation expected in a harsh but dry climate, but where the book remained closed and unused for centuries, protecting its contents. Of course, dating any manuscript palaeographically is difficult, and one can only hope for a 50 to 150 year range of plausible dates for its making. As well, even the so-called "best" manuscripts have murky and suspicious origins, and show a complex history of use, travel, correction and even abuse and neglect by various unknowable hands.

Comparative Palaeography:

One of the best checks and balances available for palaeographical dating estimates is a comparison to other existing documents of better known date and origin. That is why the little-known last few pages of another manuscript become important...

Turn to Codex Nitriensis now for a moment. This is a 6th century Greek parchment, scraped off and re-used to copy a Syriac commentary. It sits in the British Museum. Most of its text is from Luke, and this part of the manuscript has been dated to the 6th century with strong certainty.

Sometime between the late 8th and early 9th century AD, Simeon, a monk at the convent of Mar Simeon of Kartamin, copied a Syriac text for Daniel, episcopal visitor (periodeutes) of the district of Amid in Mesopotamia (see notes in Add. MS 17211, ff. 53r and 49r). We owe to this event the partial survival of several older copies of Greek works, since Simeon reused parchment sheets from which Greek text had been scraped or washed off to copy the treatise against Joannes Grammaticus of Caesarea by the author Severus of Antioch. Today, Simeon's Syriac copy survives in two manuscripts at the British Library. The Syriac text has been rebound to reconstruct the sequence of the underlying (scriptio inferior), barely visible Greek texts of a 5th century copy of Homer's Iliad (Add. MS 17210) and a 7th century copy of the Gospel of Luke (Add. MS 17211, ff.1-48) as well as a 7th or 8th century copy of Euclid's Elements (Add. MS 17211, ff.49-53).

Add. MS 17211 is, of course, better known as 'Codex Nitriensis', betraying the fact that Simeon's manuscript once belonged to the convent library of St Mary Deipara in the Nitrian Desert of Egypt. Its text, containing parts the Gospel of Luke, is also known in New Testament scholarly circles under its Gregory-Aland 'number' R or 027.

Many ancient texts survive as palimpsests, the faint remains of texts on reused parchment that sometimes reappear over time or are recovered with the help of modern technology.

6th century, 'Codex Nitriensis', a palimpsest, 9th century, containing Severus, Patriarch of Antioch, Treatise against John Grammatikos, chapters I-VIII, XX-XXI (Syriac) written over parts of the Gospel of Luke (Greek) (Gregory-Aland R = Gregory-Aland 027)

The style of the writing and caligraphy closely resembles Codex Alexandrinus and portions of Codex Sinaiticus. Here is a sample:

|

| Codex Nitriensis - Luke: Click to Enlarge |

What is rarely noted however, is that the last few pages of this palimpsest have another work hidden under the Syriac, in another script: Its a fragment of the Elements of Euclid, and it also has been firmly dated, to the 7th or 8th century:

The British Museum describes this portion as follows:

Euclid, Elementa (TLG 1799.001) , books X and XIII (7th century or 8th century)

|

| Click to Enlarge |

|

| Click to Enlarge |

How was this date arrived at? By a knowledge of the scriptorium/monastery where it came from, and most importantly, by the palaeography of its writing!

And that's the point: This style of writing has been positively identified as 8th century, and it is the very same style of writing as found in Codex W.

Textual critics had originally wanted to date Codex W as much earlier, i.e. 5th century, because of course it was an interesting copy of the Gospels with unusual readings. (It was classed as a "Caesarean" text-type by Streeter etc.).

But palaeographically, this date appears pretty unrealistic, given that the unusual style of writing has been pegged at the 7th or 8th century, at the very location where in the 4th and 5th centuries the style of Alexandrinus was produced instead.

mr.scrivener

Monday, March 7, 2011

Good quality scans of Codex Bezae

We were so disappointed that the only photos of Codex Bezae (D / 05) Cantabrigiensis were on a Muslim website, that we located better pictures and temporarily posted them here:

Codex Bezae (all 4 gospels/Acts)

You can click on them to enlarge, and they can be saved to disk by right-clicking on the popup high-res photo. The box will open to the width of your browser, so you can make them bigger if you have the screen space.

mr.scrivener

Codex Bezae (all 4 gospels/Acts)

You can click on them to enlarge, and they can be saved to disk by right-clicking on the popup high-res photo. The box will open to the width of your browser, so you can make them bigger if you have the screen space.

mr.scrivener

Thursday, March 3, 2011

Mark 1:41 - Why Jesus was angry in codex D

The Textus Receptus reads for Mark 1:41:

ο δε ιησους σπλαγχνισθεις εκτεινας την χειρα ηψατο αυτου και λεγει αυτω θελω καθαρισθητι

Here we have almost complete agreement among all important witnesses, including Aleph/B): א A B C K L W ΔΘΠ 090 f1 f13 28 33 565 700 892 1009 1010 1071 1079 1195 1216 1230 1241 1242 1253 1344 1365 1546 1646 2148 2174 Byz. Lect. Italic, Vulgate, Syr, copt Goth Arm Geo Diat. etc.

The UBS2 text notes the following variant:

ο δε ιησους οργισθεις εκτεινας την χειρα αυτου ηψατο και λεγει αυτω θελω καθαρισθητι

'And Jesus being angry at him, stretched forth his hand; and touching him, saith to him: "I will. Be thou made clean." (Mk 1:41)

The support is: D it-a,d,ff2,r1, Ephraem (it-b omits word).

Of course even with this flimsy attestation, the reading creeps into many modern versions due to "overwhelming" internal evidence (a conjectured 'harder reading' using the criterion of embarrassment).

Now however, new evidence has come to light, in part suggested by the strange Old Latin support. It is found in the previous verse, (Mk 1:40), where the text begins,

και ερχεται προς αυτον λεπρος ...

In several ancient Irish MSS we find the Old Latin/Clementine vulgate reading:

However with the following twist:

That is, there was a homoeoteleuton error as follows:

dropping 8 letters of text and causing a new word to form: leprecans.

This is a common spelling of the Old Irish word,

Jesus autem misertus ejus..., in the sense of "deplore" back-translated / corrected the Greek in Bezae to read:

οργισθεις i.e., Jesus "was angry with" or "despised" the Leprechaun, presumably for being mischievous and duplicious.

ο δε ιησους σπλαγχνισθεις εκτεινας την χειρα ηψατο αυτου και λεγει αυτω θελω καθαρισθητι

'And Jesus having compassion on him, stretched forth his hand; and touching him, saith to him: "I will. Be thou made clean." (Mk 1:41)

Here we have almost complete agreement among all important witnesses, including Aleph/B): א A B C K L W ΔΘΠ 090 f1 f13 28 33 565 700 892 1009 1010 1071 1079 1195 1216 1230 1241 1242 1253 1344 1365 1546 1646 2148 2174 Byz. Lect. Italic, Vulgate, Syr, copt Goth Arm Geo Diat. etc.

The UBS2 text notes the following variant:

ο δε ιησους οργισθεις εκτεινας την χειρα αυτου ηψατο και λεγει αυτω θελω καθαρισθητι

'And Jesus being angry at him, stretched forth his hand; and touching him, saith to him: "I will. Be thou made clean." (Mk 1:41)

The support is: D it-a,d,ff2,r1, Ephraem (it-b omits word).

Of course even with this flimsy attestation, the reading creeps into many modern versions due to "overwhelming" internal evidence (a conjectured 'harder reading' using the criterion of embarrassment).

Now however, new evidence has come to light, in part suggested by the strange Old Latin support. It is found in the previous verse, (Mk 1:40), where the text begins,

και ερχεται προς αυτον λεπρος ...

And there came a leper to him,... (Mk 1:40)

In several ancient Irish MSS we find the Old Latin/Clementine vulgate reading:

Et venit ad eum leprosus deprecans eum :

However with the following twist:

Et venit ad eum leprecans eum :

That is, there was a homoeoteleuton error as follows:

Et venit ad

eum lepr

osus depr

eum lepr

osus depr

ecans eum :

dropping 8 letters of text and causing a new word to form: leprecans.

This is a common spelling of the Old Irish word,

- leprechaun

- c.1600, from Ir. lupracan, metathesis from O.Ir. luchorpan lit. "a very small body," from lu "little" + corpan, dim. of corp "body," from L. corpus "body"

Jesus autem misertus ejus..., in the sense of "deplore" back-translated / corrected the Greek in Bezae to read:

οργισθεις i.e., Jesus "was angry with" or "despised" the Leprechaun, presumably for being mischievous and duplicious.

mr.scrivener

Tuesday, February 8, 2011

Reviews of Houghton and 4th century MS production

H. A. G. Houghton. Augustine’s Text of John. Patristic Citations and Latin Gospel Manuscripts. Oxford: OUP, 2008. (13.8×21.6), 424 p. ISBN 978-0-19-954592-6. Hardback.

The first review we quote below gives us some enlightening gems of information rarely discussed in TC circles, as to practices and options regarding book production and Scripture care and stewardship;

J. Cornelia Linde

First Review quoted above <- - Click here.

The second review discusses Augustine's use of Old Latin texts and his later adoption of Jerome's Vulgate, as well as quotations from memory. The discussion is rather complex but persistence pays off in understanding some of the difficult features of any analysis of patristic sources.

Discussion of Patristic Citation <- - Click here.

The author himself responds to these reviews with a wonderful discussion about how ancient writers like Augustine determined their texts:

Author's Response <- - - Click Here.

mr.scrivener

The first review we quote below gives us some enlightening gems of information rarely discussed in TC circles, as to practices and options regarding book production and Scripture care and stewardship;

J. Cornelia Linde

"The following chapter, ‘The Use of the Bible and the Production of Books in the Time of Augustine’, is an insightful and, again, well documented discussion of the production and diffusion of biblical texts in Augustine’s time, based for the most part on examples from Augustine’s writings.Houghton points out several noteworthy facts. So, for instance, that manuscripts of Scripture were on sale on the open market, and that churches had their own copyists and secretaries, who would usually produce books to order (p. 24) by sending a scribe in situ to transcribe a text. A side aspect, yet all the same fascinating, was the description of how minutes at council proceedings were produced by stenographers, then copied and signed by the participants (p. 28). In addition, Hugh provides some insight into questions of liturgy in churches around the year 400, especially with regard to the role of the lectores, who were responsible for both their church’s scriptural books, which they usually kept at home (p. 22), and reading the lecture at mass. A point that was not addressed by Houghton is that the lectores (p. 22, n. 2) were often children and the consequences resulting from this fact for their role. Houghton does not mention their age and whether we can assume that children were entrusted with manuscripts and their safekeeping."

First Review quoted above <- - Click here.

The second review discusses Augustine's use of Old Latin texts and his later adoption of Jerome's Vulgate, as well as quotations from memory. The discussion is rather complex but persistence pays off in understanding some of the difficult features of any analysis of patristic sources.

Discussion of Patristic Citation <- - Click here.

The author himself responds to these reviews with a wonderful discussion about how ancient writers like Augustine determined their texts:

"The nature of the Old Latin BibleCornelia asked several times about the versions of the Bible Augustine used and which texts had official sanction. Part of this is to do with the nature of the earliest Latin translations: Augustine claims in De doctrina christiana that, as I translate, anyone “who believed himself to have a modicum of ability in both [Latin and Greek] … hazarded his own translation”. In reality, surviving Old Latin versions are a lot more consistent than is often claimed, and, what we seem to have are successive revisions of a limited number of early translations.Yet the concept of versions is bound up in the wider issue of using early manuscripts for the text of the Bible. Every manuscript is different, and therefore every Bible is different. For example, a Christian community might have been using scriptural codices which did not include the story of the woman taken in adultery, or claimed that Barnabas, not Barabbas, was set free instead of Jesus, or even had that famous alternative reading in the Ten Commandments “Thou shalt commit adultery”. This would not have made any difference to the way the manuscript was used in the liturgy, or revered as sacred scripture. Clearly, more obvious copying errors would usually have been corrected pretty quickly, but plenty have been left to stand! Augustine’s comparison of manuscripts was a standard preliminary stage in working with a text [see page 18 on reading practices in antiquity], just like modern scholars should ascertain whether they are using a current edition of a work, or whether there is a corrected second edition or important subsequent material which needs to be taken into consideration.In fact, I suspect that modern attitudes to “the Bible” even after the invention of printing are not so different to those in the time of Augustine. ...Even if you take a printed Latin Vulgate or an edition of the Greek text as your archetypical “Bible”, you still have to specify which edition. None are entirely identical, and among modern translations – as with the Old Latin tradition – it can be very difficult to specify when a text is sufficiently different that it constitutes a new version rather than a variant form or light revision of an earlier version.In the light of this, I would like to suggest that authority is co-located in an overall concept of Scripture and the individual exemplars which one uses for one’s text. When Augustine says “it is written in the Bible”, how would he prove it? In the same way as he challenges his opponents in the dialogues, by inviting them to bring him a manuscript with that reading [e.g. Contra Faustum (p.18-19)]. And if they could, he then goes on to outline his text-critical criteria for evaluating that witness: how old is the manuscript? Is it accurate elsewhere? How does it correspond to Greek manuscripts?"

Author's Response <- - - Click Here.

mr.scrivener

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)